My Works

Pound

Pound

My brothers would go there to shoot the rats

that ravaged the bodies of dead strays

laid out in trenches like those I'd seen before

in pictures of Auschwitz— deep ruts spanning

the property's width behind the small cinder

block building that housed the living,

waiting animals. Once, a small black bear

paced in circles in one of the cages.

My father took me there again to choose

a kitten, my own dead beneath the wheels

of his car. And once, my bicycle crunched

up the gravel drive past the kennels

to the back of the building, where two men

in dark uniforms waited beside a truck,

a dog-sized metal box resting in the bed.

Rubber tubing ran from the closed box

to the exhaust. The engine whined softly

as the driver leaned against the fender,

smoking a Camel. Howls of laughter from

both men—a joke about something. Crushing

his smoke with his boot heel, one turned and barked

"Go home. This ain't no place for a girl." Later,

when the pound had been left to the lost

and abandoned, I returned to search

the twilight ditches for that certain dog—

impossible in the piles upon piles

of furred bodies—those that were still, and those

others darting darkly among them.

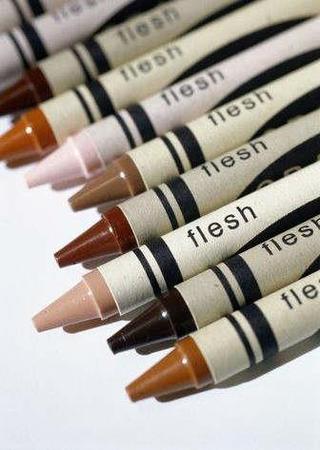

Flesh (title poem from my chapbook Flesh)

Back when everything was black and white

and even crayons had a voice

of politics and race,

art class should have been our favorite,

spoiled only by a teacher we students loathed:

her built-up shoe and leg brace emblems

of survival, her crutch a weapon

in her private war against expression

by children who wished to defy her demand:

“Make the heads the size of a grapefruit!”

Resulting in hydrocephalic figures

crowded together on rough sheets

of cheap art paper,

their bodies floating below

those cranial balloons

like kite tails made from arms and legs

and skeletal torsos.

Households of folks

with similar inflated features,

schoolyards of distended skulls at play,

toting along their appendages

like afterthoughts or unwanted offspring,

all colored from the same 48-crayon Crayola box,

all colored the same color: Flesh.

Even by the polite colored children

and the Garza’s, whose eyes were bright

Black, whose warm skin was close to Indian Red;

the only Indians we knew

were in TV westerns on Saturday night

and Saturday morning Andy’s Gang jungle flicks,

portrayed in light and dark

tones of gray by actors in pancake makeup;

even African tribesmen

carrying their fearsome spears

and shields were played by white men.

The Swede children—Anderson, Ericson,

Johnson, and Swanson—chose Periwinkle

or Cornflower for their eyes;

the German’s, David and Anne,

Prussian Blue or simple Brown.

The teacher frowned, her horn

rims’ glass glaring at children

who dared to choose Burnt Sienna

or Sepia to color the faces and arms and hands

of their bulging-mugged families.

When we were finished

small fingers smelled of paraffin

and the waxy colors were replaced

side-by-side back inside their boxes.

All around the chalk-dusted classroom

rectangles floated, taped against blackboards

and crowded with over-sized noggins,

their superfluous, atrophied bodies,

and even a school kid could see

that things were terribly out of proportion.

Where Things Came From

Summer. It seemed always

summer—hot wind driving

east from the prairies, heavy

with rain that refused to fall

to earth until it struck out

like a black snake poked one time

too many with a sharp stick,

the warning reverberations

ignored. Then slanting sheets

dropped and needles of rain

punctured the cinder dust,

stirring up that dark scent

of thirsty earth and water.

Mother lugged a washtub

to the corner of the house

beneath the gushing eaves,

to gather sweet rainwater

for the garden and the wash

while I splashed knee-deep in ditches.

But mostly it was hot. Sticky

tar boiled up black and tacky

between the lumps of limestone

gravel cast across the road,

tar that reeked of crude and burned

the feet of little barefoot girls

who dared to cross the heat

to feed the flock of neighbor’s

lambs and rub their oily heads.

Sometimes a rock would shine

like gold and hold the shadow

of a bone or fin, some tiny life

etched against the face of stone.

Then August came again.

I’d meant to ask how fishes

pressed their feathered tails to mud

a hundred million years ago

and turned to tar, then stone.

Then mother pulled brown paper

sacks over my bare feet and snapped

tan rubber bands around my

bony shins to hold the bags

in place. I tramped once more

across the gummy road to find

the meadow empty. Returned

to mother humming at the stove

as she had done each night

of my young life—the floor was mopped,

the garden picked, fresh rye

bread on the board. This I ate,

refused the liver, and never

did I ask about the lambs.

Homing

The cemetery quiet, no visitors today

save for the somber pigeon holding vigil

on the drive. Some spirit of the dead, earthbound

flight of a lost soul? A bird of common gray

and royal purple, banded on both legs—

one in white for courage, the other black

for counted losses. How many

miles from where she started, stunned

and fallen from homing into this tiny square

of ancient gravestones set far from town

in fields of drought-dried corn? But now,

the pigeon has lifted to my car window,

half-closed. Her eyes peer at the bird

mirrored in the glass; her fear a mantle

she sheds due to her great loneliness.

Even birds desire: that yearning for home

no matter where they land. Even birds,

unknowing of what they know, seek a familiar

roost—if it be a cote or prison. And I,

unwilling to leave her here where

the chestnut is a murder of crows,

where the stippled sky echoes hawk’s cry,

where the ground is snake and feral cat,

and every corn row a coyote’s trail—

even I, who craved some solitary freedom

on a course that has led me so far afield,

fold her muted wings against her body,

speak softly, and look into her orange eyes,

slip her, scrabbling, then quiet, into an emptied box.

Even I, knowing she may never find her way

back from where she came, knowing safety

is a place sometimes that is nowhere close

to home, drive out down this cobbled,

narrow lane lined with strong-armed maples

holding back the fields and the open sky.

First Published in New Southerner

Bucket Man

for James

Drive down any road here

strewn with peeled-off rubber

retreads, ubiquitous

halves of lots of pairs of

shoes, broken boards, hubcaps,

road kill in diverse states

of decay. Useful things,

too—for he slows the truck,

stops beside the pavement,

dodging oncoming cars

to cross the road. Retrieves

the prize from that weedy

muck of ditch—a bucket,

handy for carrying

sweet mash or barley to

horses, water to quench

their mighty thirsts. Buckets

from construction trucks, those

pails that held plaster and

joint compound, nails or paint,

and shortening vats from bakeries—

washed and dried—are of use

on a farm. If you find one,

hold on to that bucket

man—who better to know

the value of some lost,

some used and empty thing?

Published in A Stirring in the Dark, Old Seventy Creek Press

and Little Fires, Finishing Line Press

11/11/11

In my office at the university, another day

of grading student papers and catching up

with emails, when I hear the dreadful beat

of a funeral drum: three thunderous raps

like the last heartbeats of some dying giant.

From somewhere, the sound of taps

begins playing and I remember the last time

I heard it—that bright, cold day

in April, in Illinois, as we lay Philip

next to Robert, two plots down from Kent,

each gravestone bearing the name

of a different war. I remember what day it is.

I remember my brothers, the three of them

lying close now in cold sleep as they did

as children on winter nights in a chill house,

back when their address was the same.

As it is now: Second Avenue, Knoxville

Cemetery, as if the dead need an FPO.

Outside my office window I see the flag

and the crowd, many dressed in black.

Their heads are bowed. I press my face

against the glass and weep. Sobbing

the bagpipe begins to play “Amazing Grace,”

emptying itself again and again and again.

Echo I

Echo II

Little Fires

Event Horizon

Finalist, 2007 Rita Dove Poetry Award

In the Garden of Carnivorous Plants

June 2003

Shadow

Coal Country

Winner: 2007 Oliver Browning Poetry Award, Poesia

Winner: 2006 Passager Poet of the Year Award

Winner: 2005 Betty Gabehart Poetry Award

Finalist: 2006 Rita Dove Poetry Award

Honorable Mention: 2006 Margaret Reid Traditional Forms

Overburden, with lines from Milosz

All content copyright Christina Lovin 2019. No parts may be reproduced or used without

permission from the author.